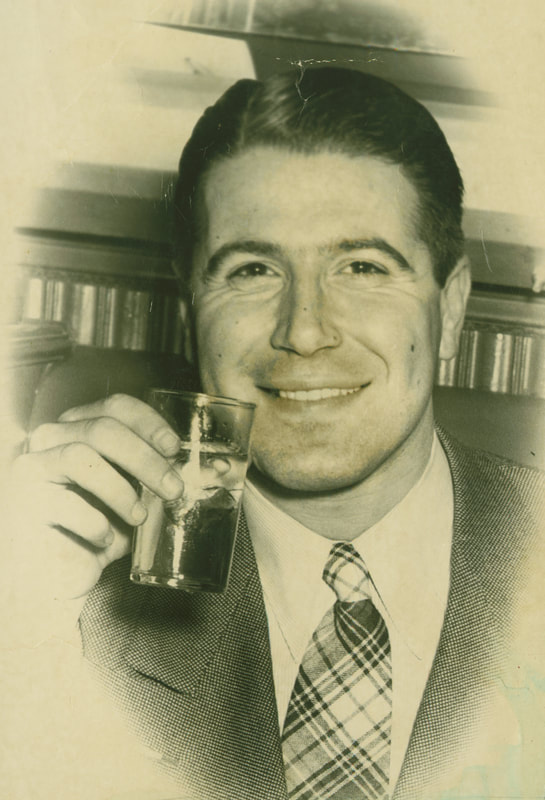

I Won’t Back Down (Tom Petty) Well I won't back down No I won't back down You can stand me up at the gates of hell But I won't back down No, I'll stand my ground Won't be turned around And I'll keep this world from draggin' me down Gonna stand my ground And I won't back down Hey baby, there ain't no easy way out Hey I will stand my ground And I won't back down And I won’t back down We buried my father on the afternoon leading up to Rosh Hashanah in 2003. Now, some rabbis say the High Holy Day season begins with Tisha B’Av – in the middle of the summer. Some say it begins with the Selichot service, a week before Rosh Hashanah. I have always believed the former but about a week ago, it occurred to me that whatever I might think I believe, since 2003, the High Holy Day season smacks me up the side of my head, on the day of my father’s yahrtzeit. Avshalom Saul Smith (yeah you heard me right), Avshalom Saul Smith alav hashalom, may peace be upon him, was a civil engineer. Now, when I say alav hashalom, may peace be upon him, I am wishing peace upon a man whose name Avshalom means father of peace. Suffice to say no name ever fit a man quite so well. Avisholum as some of his relatives called him, began his civil engineering career helping to build the New York Thruway and then went to work for a company named Porter & Ripa in Newark, NJ, where he was involved in the building of the Garden State Parkway. Porter & Ripa did a lot of work for the state of NJ and in the late 70’s it was discovered that the company had been taking the state of New Jersey to the cleaners—embezzling a million dollars by altering timesheets. Unfortunately, my father’s signature was at the bottom of a lot of these timesheets and he was asked to appear before a grand jury. Just to be clear, my father signed these timesheets before they were altered. He did nothing wrong, and perhaps to ensure his “loyalty,” someone very high up in the company asked my father to lie to the grand jury. I don’t think I need to say anything more than point you to any episode of the Sopranos to help you understand exactly what was going on. In the end my father did the right thing – really the only thing he knew how to do. He told the truth. Now, it’s easy to say that my father did the right thing, but as I got older I came to understand exactly what it took to do this right thing. Clearly, it was dangerous to lie to a grand jury. But it was just as dangerous, if not more so in this case, to defy this person so high up in the company and possibly put yourself and your family at risk. But again, my father had no idea how to lie. Telling the truth was all he knew how to do. As Tom Petty wrote in the song I began with, my father would not; could not back down from his ethical beliefs. Soon after, the company was taken over by forces that probably weren’t much better and many in the company, including my father, who at the time was 57 years old, were fired. But, Avshalom Saul Smith was an excellent engineer and it didn’t take him long to find a job, despite his age. He went to work for the Louis Berger Company in E. Orange, NJ. Now, East Orange wasn’t exactly an upgrade neighborhood-wise from Newark but it was definitely an upgrade in job opportunity. The Louis Berger Company was an international engineering firm and not long after he joined the company my father was sent to Portugal for a month. Soon after that, Louis Berger bid on a job in Israel to build an air base in the Negev. The air base needed to be built to replace an existing one in the Sinai, which would soon be given back to Egypt as part of the Middle East Peace Accords. The Louis Berger Company won the bid and when my father was named project engineer for this job, my parents moved back to Israel for two years. For me, this has always been a story about doing the right thing no matter the cost and I’ve always held this story up as a model for how I needed to live my life. My father was generally a quiet man but his actions spoke way louder than his words. This is also a story about enduring difficult times on the path to finding your destiny and I don’t think my father could have found a more perfect destiny if he had chosen it himself. His destiny meant returning to the land of his childhood, to the land his grandparents made their home in the 1890’s and perhaps most importantly, his destiny was to help make Israel a more secure state. That destiny would not have happened had Porter & Ripa been an honest company. In a well-known Talmudic story (BT Shabbat 31a), a non-Jew asks Rabbi Shammai to convert him saying: convert me on condition that you teach me the entire Torah while I am standing on one foot. Shammai pushed him away….. The same gentile came before Rabbi Hillel and Hillel converted him. He said to the man: That which is hateful to you do not do to another; that is the entire Torah, the rest is commentary. Go study.[1] If we are looking for a single Jewish principle defining how we should behave, this isn’t a bad choice. That which is hateful to you don’t do to others? If you hate it when others gossip about you, then don’t gossip about others. This is the whole Torah? Well, while monotheism is at the heart of Judaism, if one believes in God but doesn’t practice what Hillel preaches, how can that person be considered a religious Jew? The rest is commentary? Well, all Jewish laws should in some way reinforce and at the very least, not negate, ethical behavior. Go study? Understanding how to act appropriately is not necessarily a simple matter. One of the more famous verses in the Torah says: Justice, justice you shall pursue. Reading this verse is not enough. We need to study and figure out what exactly constitutes acting justly.[2] Hillel wasn’t the only rabbinic sage to define Judaism in ethical terms. A century after Hillel Rabbi Akiva, the leading rabbi of his age, taught that the verse Love your neighbor as yourself is the major principle of the Torah.[3] Like Hillel, Akiva believed that treating others fairly cannot be seen as one worthy act among many, but as the most important act.[4] Certainly, a significant ethical essence or contribution made by the Torah is the Ten Commandments. In addition to obligating Jews to affirm God, observe Shabbat, ban idolatry, and not take God’s name in vain, the Ten Commandments prohibits murder, adultery, stealing, bearing false witness, and coveting. The Torah may talk about sacrifices, holidays, circumcision, etc. but the Ten Commandments are overwhelmingly moral rules regulating relations between human beings. Morality is the essence of Judaism.[5] Even before the Ten Commandments the Torah emphasized ethical behavior. In explaining Abraham’s mission in the book of Genesis, God says: כִּ֣י יְדַעְתִּ֗יו לְמַ֩עַן֩ אֲשֶׁ֨ר יְצַוֶּ֜ה אֶת־בָּנָ֤יו וְאֶת־בֵּיתוֹ֙ אַֽחֲרָ֔יו וְשָֽׁמְרוּ֙ דֶּ֣רֶךְ יְיָ֔ לַֽעֲשׂ֥וֹת צְדָקָ֖ה וּמִשְׁפָּ֑ט : For I have singled him out in order that he may instruct his children and his posterity to keep the way of the Lord by doing what is right and just. (Gen. 18:19) Abraham in turn, holds God to the same principle. When he fears God is acting unfairly in planning to destroy the cities of Sodom and Gomorrah, Abraham challenges God: Shall not the judge of all the earth act with justice? (Gen. 18:35)[6] Later on in the Tanakh, the Prophet Micah asks: What does the Lord require of you? To do justice, love mercy, and walk humbly with God (6:8) Micah doesn’t focus on faith, sacrifices, or other rituals but rather on justice, compassion, and humility. He doesn’t say walk arrogantly with God, but walk humbly with God.[7] How timeless are the words of the prophet Jeremiah: Let not the wise man glory in his wisdom; Let not the mighty man glory in his might; let not the rich man glory in his riches. But one should only glory in this: that he understands and knows righteousness on the earth. For in these I delight, says the Lord. (Jeremiah 9:22-23)[8] There are certainly examples in the Tanakh of people who refused to follow immoral orders. Perhaps one of the more well-known stories is that of the midwives Shifra and Puah, who refused to follow Pharaoh’s order to kill the baby boys born to the Israelite women (Ex. 1:15-21). When Pharaoh confronts them they tell him a tale -- by the time we got to the women they had already given birth and we weren’t able to out carry your orders. It’s unclear whether Shifra and Puah are Israelite or Egyptian midwives. But either way, it took great courage to stand up to Pharaoh.[9] On the flip side is the story of David and Bathsheba. After David impregnates Bathsheba wife of Uriah, one of David’s soldiers, he plots to cover up what he has done by bringing Uriah home from battle to sleep with his wife. But Uriah swearing loyalty to the troops, doesn’t comply. So David sends him back to the front and orders his military commander Yoav, who also happens to be David’s nephew, to make sure Uriah is killed in battle. Yoav, unlike Shifra and Puah, is not defiant. He follows David’s order and eventually Uriah is killed on the battlefield. David then marries Bathsheba. As the Bible goes so goes current events. Each and every day, the news is filled with stories of people who like my father, do the right thing fully aware of the possible cost to their lives. Even if they aren’t putting their lives on the line, they know the life of this country is on the line. They do it knowing that while the cost for them could be great, the cost to our country could be even greater. On the other hand, there are certainly other public servants for whom that kind of courage has been sorely lacking. Holocaust survivor and psychotherapist Victor Frankl wrote: We who lived in concentration camps can remember the men who walked through the huts comforting others, giving away their last piece of bread. They may have been few in number, but they offer sufficient proof that everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms – to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.[10] These days, perhaps more than any other in our lifetime, we need to choose wisely. Well, I know what’s right I got just one life In a world that keeps on pushin’ me around But I’ll stand my ground And I won’t back down Hey baby There ain’t no easy way out Hey I will stand my ground And I won’t back down. L’shana Tova u’metukah Wishing all of you the happiest, healthiest and sweetest of New Years. [1] Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 31a [2] Joseph Telushkin. A Code of Jewish Ethics, vol. 1. (New York: Random House, c2006) 10-11. [3] Jerusalem Talmud Nedarim 9:4 [4] Joseph Telushkin. A Code of Jewish Ethics, vol. 1. (New York: Random House, c2006) 12. [5] Ibid. 13 [6] Ibid [7] Ibid. 211 [8] Ibid. 14-15 [9] Ibid. 30-31 [10] Ibid. 30 This week's Torah portion, Bechukotai, the last portion in the book of Leviticus, contains what are called the Tochecha, verses of rebuke. These verses, which are chanted quickly and in a low voice, contain some pretty difficult stuff – curses heaped upon the Israelites if they do not follow God's laws. The curses include things like sowing seed to no avail and making the land desolate. While the list goes on and on, today I can't help but notice one particular curse that will befall the Israelites if they fail to follow God's laws. I will let loose wild beasts against you and they shall bereave you of your children (Lev. 26:22). What precisely are the sins committed that would bring on this particular curse is difficult to fathom. But today, two days after yet another mass shooting in an elementary school – Senator Chris Murphy of Connecticut made the case for the sin of doing nothing when he said to his colleagues: "Why do you spend all this time running for the United States Senate – why do you go through all the hassles of getting this job, of putting yourself in a position of authority – if your answer is that, as this slaughter increases, as our kids run for their lives, we do nothing?" Elie Wiesel once wrote, "What hurts the victim most is not the cruelty of the oppressor, but the silence of the bystander." Even worse is when those silent bystanders are many of our elected officials, whose job it is to take action. To them I say, "No more silence. End gun violence." Shabbat Shalom. Ellie  When all else fails follow directions I sometimes joke that I am good at following directions. For the most part this is a true statement, although I have to admit when I joke about it, that often means I’d rather ignore the instructions given to me. It’s also true that every once in a while that joke morphs into a twinge of rebelliousness. When that happens I typically do not follow directions. But joking or not, for the most part I’m ok with it. For instance, if I purchase an item that includes written instructions, I will read them to make sure I understand how to put together or operate what I just purchased. If I am filling out a form or an application, I will also take care to properly fill out the information required. And…… if the governor instructs me to wear a mask in order to keep others around me safe, I’m on it. In this week’s Torah portion Chukat, we read: וַיָּבֹ֣אוּ בְנֵֽי־יִ֠שְׂרָאֵ֠ל כָּל־הָ֨עֵדָ֤ה מִדְבַּר־צִן֙ בַּחֹ֣דֶשׁ הָֽרִאשׁ֔וֹן וַיֵּ֥שֶׁב הָעָ֖ם בְּקָדֵ֑שׁ וַתָּ֤מָת שָׁם֙ מִרְיָ֔ם וַתִּקָּבֵ֖ר שָֽׁם: וְלֹא־הָ֥יָה מַ֖יִם לָֽעֵדָ֑ה Then came the people of Israel, the whole congregation, into the desert of Zin in the first month; and the people abode in Kadesh; and Miriam died there, and was buried there. And there was no water for the congregation. In one verse Miriam dies and in the next the Israelites are without water. The rabbis surmised this must mean water is connected to Miriam --- that the water the Israelites enjoyed in the desert was due to the merit of Miriam who watched over her infant brother Moses floating down the Nile in a basket. Now that she has died, there is no more water. The Israelites are worried and that leads to complaining. Moses and Aaron as usual, take the complaints of the people to God, expecting God to yet again rail against the Israelites. Instead, God simply tells Moses to take his rod, gather the community and in front of them, order the rock to burst forth with water. It looks like Moses is going to follow God’s instructions, but then instead of speaking to the rock he speaks to the Israelites and says: Listen you rebels, shall we get water for you out of this rock? (Num. 20:10) Then, rather than speak to the rock he hits it. So, not only does Moses not follow God’s directions, he seems to imply that he and his brother Aaron rather than God are responsible for procuring water from the rock. If I choose to ignore instructions that will help me put together a bed frame or a lamp, there’s a good chance both the frame and the lamp will never function properly. If I don’t fill out a college application form according to instructions, there’s a good chance I will not be considered by that college. If I hadn’t followed the Governor’s instructions and chose to not wear a mask this past year, there may have been a chance I would have helped to spread COVID. When Moses chooses to ignore God’s instructions, the Israelites are not punished for Moses’ actions. They do get the water they so desperately need. However, God tells Moses that because he and Aaron did not trust God enough to affirm God’s sanctity in the sight of the Israelite people, neither he nor his brother will be allowed to enter the Promised Land. Whatever Moses was trying to accomplish by hitting the rock, his plan backfired. Being denied entry into the Land of Israel was a high price to pay for his actions. Moses learned a little too late that when all else fails follow directions. If you are interested in learning more about Moses hitting the rock, come and join us for Shabbat services this Friday evening at 7:30pm. Shabbat Shalom, Ellie  Time Takes Time Behaviors cultivated over many years are hard to change. In order to transform our lives, it is necessary to overcome what psychologist Dr. Jennifer Kunst calls a misconception – the belief that we need the very thing we are trying to give up. An alcoholic has to overcome the belief that he or she needs a drink and victims of physical abuse need to overcome the belief that they need their abuser. Even when we know our behavior needs to change we tend to resist that change. As Dr. Kunst writes: the mind is like a rubber band; you can easily stretch it temporarily, but it snaps back to its resting position. We resist change. We like to believe that continuing to do what we’ve always done will keep us safe, while changing our behavior could put us in danger. In this week’s Torah portion, Bamidbar, the first portion in the book of Numbers, the Israelites are themselves in the midst of a behavioral change. After experiencing the events at Sinai they are now transitioning to the daily routines necessary for wandering through the wilderness. In this week’s portion that means organizing into a military camp as a way to face the dangers they might come upon during their journey. Later in the Book of Numbers the Israelites will find it more difficult to adapt to the harsh wilderness and loudly state their desire to go back to Egypt: וְלָמָ֣ה יְ֠יָ֠ מֵבִ֨יא אֹתָ֜נוּ אֶל־הָאָ֤רֶץ הַזֹּאת֙ לִנְפֹּ֣ל בַּחֶ֔רֶב נָשֵׁ֥ינוּ וְטַפֵּ֖נוּ יִהְי֣וּ לָבַ֑ז הֲל֧וֹא ט֦וֹב לָ֖נוּ שׁ֥וּב מִצְרָֽיְמָה: וַיֹּֽאמְר֖וּ אִ֣ישׁ אֶל־אָחִ֑יו נִתְּנָ֥ה רֹ֖אשׁ וְנָשׁ֥וּבָה מִצְרָֽיְמָה: And why has the Lord brought us to this land, to fall by the sword, that our wives and our children should be a prey? were it not better for us to return into Egypt? And they said one to another, Let us choose a chief, and let us return to Egypt. (Num. 14:3-4) As the Life Recovery Bible notes: All of us wish that our recovery would involve a dramatic escape from slavery and immediate entrance into the Promised Land. We would love to leave out the wilderness experiences in between. But growth and recovery occur within the wilderness. It is in the wilderness that we come to terms with who we really are. Even after Sinai and the receiving of the Ten Commandments, the Israelites still struggle to overcome the very thing they are trying to give up—Egypt. But that’s ok because time takes time. Shabbat Shalom, Ellie  I thank you for my life, body and soul Help me realize I am beautiful and whole I’m perfect the way I am and a little broken too I will live each day as a gift I give to you Written by Dan Nichols, this song Asher Yatzar (He Who Has Fashioned), is a commentary on a daily prayer of the same name: Blessed are You our God, Sovereign of the universe, who fashioned people with wisdom, and created within them many openings and many cavities. It is obvious and known before Your throne of glory, that if but one of them were to be ruptured, or but one of them were to be blocked, it would be impossible to survive and to stand before You. Barukh Ata Adonai rofeh khol basar u’mafli la’asot -- Blessed are You God, who heals all flesh and acts wondrously. Expressing thanks for the continued functioning of our bodies that allows us to awaken on any particular day, this prayer Asher Yatzar acknowledges gratefulness to God for the gift of life. The song Asher Yatzar also acknowledges God for our lives, our bodies, our souls. But it doesn’t stop there-- I’m perfect the way I am and a little broken too. In other words, my body may ache, I may need to lose a few pounds, I may have a blemish somewhere, but I’m perfect the way I am. There’s a saying in the 12 Step/recovery community; progress not perfection. Not only aren’t we perfect but perfection just isn’t the goal. Perfection is elusive but it doesn’t matter. I’m perfect the way I am and a little broken too. Perfection includes being partly broken. In their book The Spirituality of Imperfection, Ernest Kurtz and Katherine Ketcham write: Spirituality’s first step involves facing [one’s] self squarely, seeing one’s self as one is: mixed up, paradoxical, incomplete, and imperfect. Flawed-ness is the first fact about human beings In this week’s Torah portion Emor, we find a somewhat different approach to perfection —at least when it comes to the priesthood. Also called Torat Kohanim, the priest’s manual, Emor describes the priestly lifestyle, one which through their various ritual obligations and restrictive way of life, sets priests apart from the rest of the Israelites. But even among the priests not everyone is created equal when it comes to those ritual obligations. No man of your offspring throughout the ages who had a defect shall be qualified to offer the food of his God……no man who is blind or lame, or has a limb too short or too long. No man who has a broken leg or a broken arm, or who is hunchback or a dwarf, or who has a growth in his eye….. shall be qualified to offer God’s gift…….he shall not enter or come behind the curtain or come near the altar, for he has a defect. (Lev. 21:16-21) Wow! I find these verses to be a bit troubling. It’s troubling enough that one has to be born into the priesthood in order to be a priest but to then be rejected because of characteristics over which one has no control is even more troubling. And to add insult to injury, priests are required to adhere to strict rules of conduct. For instance, they cannot marry a divorcee, shave any part of their heads, cut the side-growth of their beard, or make gashes in their flesh. Now, it’s true that even in our day there are many professions with strict rules of entry – jockeys for example can’t weigh more than 126 lbs. in order to compete in the Kentucky Derby. To be a pilot in the Air Force ROTC you have to have a standing height of 64 to 77 inches and a sitting height of 34 to 40 inches. But these are really requirements they are not defects. In our society we frown on discriminating against those with certain blemishes or defects. In fact, we have laws that protect this type of discrimination and yet the desire and the pressure we place on achieving perfection while not established as law, is no less prevalent than it was in the days of the Kohanim. Today we hear for instance about the pressure to be thin, the pressure to have a perfect nose, the pressure to be wrinkle-free. The rabbis like to explain away this section of the Torah by reminding us that a Kohen not only represented the people to God but God to the people. In presenting God to the people it was essential that the priest be “perfect” both spiritually and physically. But this kind of perfection just doesn’t resonate so well to our modern ears. Our modern ears hear instead how God doesn’t demand perfection from us-- how God instead demands we be the best we can be- no more no less. Truthfully, being our best is hard enough. Being our best is a daily struggle. Progress not perfection. Former Commissioner of Baseball Francis T. Vincent, Jr. once said: Baseball teaches us, or has taught most of us, how to deal with failure. We learn at a very young age that failure is the norm in baseball and, precisely because we have failed, we hold in high regard those who fail less often – those who hit safely in one out of three chances and become star players. I also find it fascinating that baseball, alone in sport, considers errors to be part of the game, part of its rigorous truth. Progress not perfection. In Leonard Cohen’s classic song Anthem, he clearly references this week’s Torah portion and priestly perfection in presenting an offering to God, by reminding us how our imperfections help us to become the best we can be: Ring the bells that still can ring, Forget your perfect offering, There is a crack in everything, That’s how the light gets in. Shabbat Shalom. Ellie |

Archives

October 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed